Kartvelological Summer School:

Effective Tool of Integration Manuscript Heritage in Educational Area

Kartvelological Summer School:

Effective Tool of Integration Manuscript Heritage in Educational Area

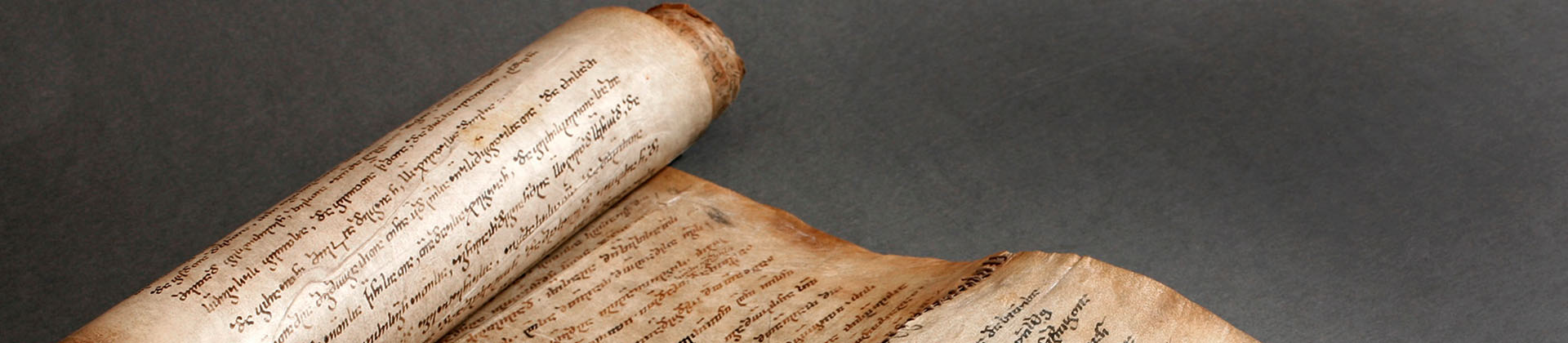

Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts has a significant experience in Kartvelological (Georgian) studies and in the study of Georgian written heritage. International Seasonal School introduces young Georgian and foreigner researchers with the gained knowledge and experience.

National Centre of Manuscripts’ Kartvelological International Summer (Seasonal) School is intended for foreign and Georgian researchers and students interested in Georgian history and culture, especially in Georgian script and manuscript heritage, and a general interest in medieval studies.

The School program is focused on the topic of Georgian manuscript. Program highlights Georgian

manuscript as a valuable source for studying Georgia’s cultural and political history in the Middle Ages.School program is structured in a way to assist listeners to understand that studying the Georgian manuscripts implies studying of political and cultural issues linked with Georgia in the context of cultural dialogue between east and west.

Training modules cover key areas of written heritage studies. Prominent Georgian scholars, who have been working for decades and have been studying unique written heritage at the Centre, share results of their researches and methodology to the participants of the project. Foreign researchers and compatriot scholar involved in the project focus attention on interpretation of archival documents which concern Georgia and are preserved in Georgia as well as abroad.

Participants are able to get acquainted with the main directions of research of the Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts (Ancient Georgian Philology, Source Studies, Archival Studies; Medieval Manuscript Culture, Restoration-Conservation, Digitalization, etc.); they are given an opportunity to see the collections preserved at the depositories of the Centre. Through lectures, discussions, interactive program, workshops, and informal meetings students can establish valuable contacts with the scholars of the Centre as well as with invited researcher, encouraging further study of the manuscript heritage.

The working language of the school is English. Lectures and other activities are held with the support of simultaneous translation. The school graduates are given the certificates.

Academic Program

Module 1. Georgian Manuscript

This module will provide information about old Georgian scriptoriums, writing materials and tools of Georgian manuscripts, miniatures and décor and manuscript book covers. The course also contains the following issues: essential structure of manuscript books (colophons, elements of text, philological-codicological analysis), a review of the history of Georgian secular and ecclesiastical literature and manuscript collection.

The students will be able to see unique manuscript collections that are preserved in the National Centre of Manuscripts. There are up to 10,000 Georgian manuscript books (5th-19th centuries) including 4,570 palimpsest pages and up to 4,000 foreign (Arabic, Turkish, Mongolian, Ethiopic, Armenian, Greek, French, German, Hebrew, etc.) manuscripts.

Module 2. Georgian Script

This module includes both theoretical and practical courses.

Theoretical courses of the first module will discuss the following issues: creation of the Georgian script; development and stages of the script (Asomtavruli-Majuscule, Nuskhuri-Minuscule, Mkhedruli-Military), Georgian epigraphy, the Georgian alphabetical system of chronology, Georgian calligraphy and schools of Georgian calligraphy.

Module 3. Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts

This module will introduce the organizer of the Summer School—the National Centre of Manuscripts. The National Centre of Manuscripts will be presented as a unique institution which at the same time houses the biggest depository of ancient samples of Georgian script, a library of old and recently printed books and an important research centre of manuscript inheritance in Georgia. Students will also be introduced to the Georgian and foreign language manuscript collection and archival funds. Students will have a chance to inspect the digitization process in a modern laboratory where digital copies of manuscripts are made and observe the work of specialists in the restoration-conservation laboratory.

In this module there are two workshops. In the first workshop the students will be given an opportunity to participate in the restoration-conservation process, specifically in the simulation of restoring deteriorated leaf. In the second workshop the students will learn how to create paper using ancient techniques.

Module 4. Georgian Historical Documents

This course analyzes the structure and types of historical documents and their constituent structural elements. Examples that will be examined will be taken from the rich collection of the National Centre of Manuscripts which includes 40,000 Georgian and 5,000 foreign-language documents (10th -19th centuries). Attention will be focused on the calligraphic peculiarity of the historical documents.

The students will have the possibility to see historical-document collections that are preserved in the National Centre of Manuscripts.

Module 5. Georgian Printed Books

This course consists of information about the old Georgian printed books. Students will learn about the creation and development of the Georgian font.

During this module, participants will have the opportunity to see rare-book collections of the National Centre of Manuscripts.

Module 6. Private Archives of Georgian Writers and Public Figures

Students will have a chance to inspect personal archives of writers and public figures gathered at the National Centre of manuscripts.

Lectures Annotation

David Shengelia

PhD in Philology

Senior Research Associate,

Department of Codicology and Textology,

Research Interests: Ancient Georgian literature; Byzantology; Patrology; Translations of Arsen of Ikhalto;

Publications: 10

Main Publications:

Old Georgian Ecclesiastical Literature

European scientists about the importance of the ancient Georgian literature:

Greek mythology and Georgia

So, Colchis is steadily observed in the Greek mythological memory as a highly developed country which is closely related with Greece and even more with the pre-Greek – Minoan civilization.

Continuation of the Greek-Georgian cultural connections after the Christianization of Georgia:

Khanmeti texts (fragments of the OT and NT, Protoevangelium of James, Khanmeti Lectionary (VII c.[3]), Khanmeti Polykephalion…) are preserved in the inner layers of the palimpsests.

The colophon of St. Saba (532 y.) witness that during given period Georgians lived in the Holy Lavra of St. Saba, in Palestine, and had Gospel, Apostolic and other liturgical texts in their own language[4]. So, it is obvious, that since IV century Georgians have translated all of the main texts of Christian literature.

Some books of the Old Testament (Isaiah, Khanmeti Ezra I) are translated into Georgian directly from the Lucianic recension of the Septuagint, unlike the old Armenian Bible which is translated from Hexaplaric one.

In the same period original hagiographical texts such as the “Martyrdom of the Holy Queen Shushanik” (476-486), “Torturing of Evstati Mtskheteli” (VI c.), and “The Martyrdom of Abo Tbileli” (VIII c.) were also created.

The first completed codex containing the Georgian version of the Bible (978).

III. Mount Athos

The foundation of Iviron Monastery (980-983).

Ioane and Eptvime (955-1028) Mtatsmindeli.

The translation process into Georgian gets systematic preplanned character.

The translation of Eptvime Mtatsmindeli: Commentaries by St. John Chrysostom on the Gospels of Matthew and John; Corpus of Gregory of Nazianzus; Corpus of Maximus the Confessor, hagiographical texts…

Adaptation of the translated texts – Translation technique of Eptvime Mtatsmindeli.

George Mtatsmindeli (1009-1065) was a translator and a public figure. He was greatly appreciated by the Byzantine Emperor and by the Patriarchs. He managed to defend the independence of the Georgian Church from the Greek Hierarchs. He translated a lot of Greek texts into Georgian. Some originals (such as Menaion and Athos Tipikon) of his translations are lost and these texts are available only through his renderings.

Efrem Mtsire (XI c.) _ The founder of the Georgian Hellenophile Translation School on the Black Mountain, the translator of huge number of works (Corpus of works by Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite, Corpus of works by Gregory of Nazianzus, “De fide Orthodoxa” by John Damascene Etc.). His colophons are of the great importance, because they give us large information about the Greek and Georgian literacy, Lexicology and Paleography.

Arsen Ikaltoeli (XI-XII cc.) _ the second eminent figure of the Georgian Hellenophile School. He graduated from Mangana Academy in Constantinople and at the same time performed his first translation. He drew up also Compendium of Christian dogmatic thinking “Dogmatikon”.

[1] A. Harnack, Forschungen auf dem Gebiete der alten grusinischen und armenischen Litteratur, Sitzungsberichte der preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 39 (Berlin, 1903), 840.

[2] Khanmetoba – grammatical phenomenon which was essential for the old Georgian literary language in the V-VII centuries. The chronology of this grammatical phenomenon is defined thanks to the dated Epigraphic monuments (Bolnisi Sioni (494-496); Jvari monastery of Mtskheta (591-600); Church of Ukangori (V-VII cc.); Georgian Monastery in Palestina (VII c.) Discovered by Virgilio Corbo) which are written according to these linguistic rules.

[3] Athanasius Renu thinks that Georgian version of Lectionary preserves V-VIII literary stage of the Greek Lectionary.

[4] E. Kurz, Das Typikon des heiligen Sabbas, Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 3, 1894, 167-170, here: 169.

Dali Chitunashvili

PhD in Philology

Senior Research Associate,

Department of Scientific and Education Programs for Manuscript Studies,

Research Interests: Georgian Studies, Armenian Studies

Publications: 15

Main Publications:

Collections of Georgian Manuscripts Abroad

The largest collections of Georgian manuscripts are kept at the Georgian National Center of Manuscripts, however, there are many other Georgian manuscripts kept at foreign depositories.The largest centers where Georgian manuscripts are currently preserved: Iviron Monastery of Mount Athos, the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, and the Monastery of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem. Over the centuries, each center was a place where cultural and educational activities were carried out. Simultaneously, Georgians were creating and protecting the rich manuscript heritage.

In addition to the three important centers mentioned above, Georgian manuscripts are also preserved in different institutions in the world, such as: Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Paris), Bodleian Library, Cambridge University Library (Great Britain), University Library of Graz, Austrian National Library, and different libraries in the United States of America. During the post-soviet era, the richest depositories of Georgian manuscripts are in Moscow and Saint-Petersburg (Russia).

During this lecture, the author will share the significance of the Georgian manuscripts, the interests and popularity among scholars, and the reasons they were placed in various locations.

Dali Chitunashvili

PhD in Philology

Senior Research Associate,

Department of Scientific and Education Programs for Manuscript Studies,

Research Interests: Georgian Studies, Armenian Studies

Publications: 15

Main Publications:

Creation of Georgian Script: Stages of its Development

The Georgian script uses a phonemic alphabet, where each phoneme is represented by a corresponding grapheme. There are two groups of sources which narrate the provenance of the Georgian script – Georgian and Armenian.

According to the Georgian tradition, the alphabet was created in the beginning of the third century B.C. Some sources even indicate a more precise date – 284 B.C.

According to one group from the Armenian sources, the Georgian alphabet was created around 429 A.D. by an Armenian monk Maštoc‘.

In modern scholarship various theories persist concerning the Georgian script and its provenance. In Georgian studies two theories have been the most popular: the ‘Semitic’ (Phoenician) theory, which claims that from the point of view of their shape, letters of the Georgian alphabet reveal affinities with a ‘Semitic’ prototype. But for the proponents of this theory, the sequence of the alphabet follows the archaic Greek model (6th c. B.C.); another theory asserts that from the point of view of sequence and shape of the letters the Georgian alphabet was created according to the Greek model after the official Christianization of Iberia in the early 4th century.

Unambiguously dated monuments of Georgian writing are attested from the fifth century only. Some inscriptions are even dated by their discoverer to the 1st-3rd cc. A.D. Such dating is not accepted by the majority of scholars.

The Georgian alphabet is preserved in three forms: rounded capitals (mrglovani asomthavruli), edged minuscule (kuthkhovani nuskhuri) and the so-called military script (mkherdruli). The first two were mainly used for Church writing (hence their alternative name – priestly), and the third type had mainly a lay usage. Traditionally the three writing styles are chronologically distributed in the following way: Capitals – 5th-9th cc., Minuscule – 9th-11th cc., and Military from the 11th c. onwards. This scheme needs certain adjustment as according to new data, samples of dated military script are attested even in the 9th century. It is usually considered that the second form of the Georgian script (kuthkhovani nuskhuri) developed from the first, and that the third developed from the second.

The old Georgian alphabet also represented numerals and included 38 letters. In the nineteenth century five functionless letters were removed and nowadays only 33 are left. The Georgian alphabet was used in the Georgian state language; for a short while it was also adapted for Abkhazian and Ossetian languages.

Darejan Gogashvili

PhD in Philology

Senior Scientist, Restorer at the Georgian National Museum (GNM), Collection Management and Conservation Department

Research Interests: Codicology; Textual study; Book Art; Chemistry; Restoration/conservation

Publications: 14

Main Publications:

1.Identification of a Chased Book-Cover Kept in Lahili Church. Bulletin of the Georgian National Museum. III (48-B). 2012

3.Several issues on the Conservation of the Papyrus Collection at the National Centre of Manuscripts. Proceedings. International Symposium – Georgian Art in the Context of European and Asian Cultures. Georgian Arts and Culture Center. 2009.

Writing Materials and Means for Creating Georgian Manuscript

Common writing material was made from paper, papyrus, and animal skin: basically from sheepskin, goatskin or calfskin.

Papyrus in Georgian is known as “Wili’’ (“Chili”). It was not used in Georgia as a writing material. There are only two Georgian manuscripts and both of them are of Palestinian origin: the Collection of Songs (9th century) and the Psalm (9th-10th centuries). The Collection of Songs is in the form of a Codex in three volumes and contains alternating sheets of papyrus (194 p) and parchment (129p). Palimpsests, ancient Georgian manuscripts written on parchment, are from the V-VIII centuries. The ancient Georgian manuscripts executed on paper in Georgia are from the XI century.

The essence of writing material (papyrus, parchment), the method of their preparation and use, and technical and technological processes are discussed in the lecture. The method of codex and roll purveyance is discussed in detail. Attention is paid to parchment and its preparation as writing material. Certain expressions are explained (”Parchment creation”, ”preparing”, “Golden stem” , Book of skin, etc.) and are discussed in connection with Byzantine, Armenian and Eastern data.

Text was written with pen and ink (writing-dye) on materials such as papyrus, parchment and paper. The main text of the manuscript was written with dark black or brown ink. The following types of ink are discussed in the lecture: iron gall ink, carbon black. Data about their preparation and composition in Georgian literary texts and appropriate terminology (”ink”, ”black”, ”drug”, “soot”, ”black dye”, ”copperas/iron vitriol”, etc.) are included. Attention is also paid to the composition of the ink in palimpsest texts.

Gold was almost always used while creating the richly illuminated manuscripts. Gold leaf and gold ink were made from gold, which were used for writing capital letters, titles and beginnings of the texts. In some cases, certain parts of the text, background in decorative art of the book, ornamental details, etc. were also illuminated with gold. Methods of preparation and use of gold-ink and appropriate terminology are discussed in the lecture: ”gold ink”, ”golden ink”, ”gold”, ”golden water”, ”golden leaf”, ”sharpening/plastering”, etc.

Along with gold leaf and gold ink, coloured writing-dyes (red, blue, green) were used to distinguish certain special places. They were also used in miniature art. Methods of preparation and use of colored-ink are discussed in the lecture. Attention is paid to the names: ”red”, ”red ink”, ”cinnabar”, ”vermilion”, ”minium’’(red lead) , ,,sandaraca”, ,,Auripigmentum’’, ”verdigris”, etc. Appropriate Latin, European, Russian and Eastern terms are included.

Darejan Kldiashvili

PhD History

Senior Scientific Employee

National Centre of Manuscripts

She has extensive experience of studying the historical documents and manuscript collections, including work on the colophons to the manuscripts, historical documents, inscriptions, family genealogies, as well as different aspects of the medieval history of Georgia and Monastic Centers. On these issues she has published monographs and essays both in local and western periodicals.

She is one of the compilers and editors of the encyclopedic, multi-volume Prosophographic Dictionary (vols. I-IV, 1991-2007), which bring together all the extant evidence about historical persons referred to in Georgian historical documents of the eleventh to seventeenth centuries.

Since the 1980s she has supervised the recording of the numerous painted inscriptions and graffiti in the cave monasteries of the Gareja desert (East Georgia). This work formed the basis of the Corpus of Gareja Inscriptions (vol. I, 1999).

In recent years she has been working on Georgian monastic synodika preserved in the liturgical manuscripts of the monasteries of historical South Georgia (Tao-Klarjeti) and of the Georgian church at St. Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai (vol. I, 2008).

One of the large-scale projects implemented under her supervision is ‘Georgian, Persian and Ottoman Illuminated Historical Documents in the Depositories of Georgia;’ website: www.illuminateddocument.ge (published in 2011: Illuminated Historical Documents in the Depositories of Georgia, Edited by Darejan kldiashvili, 288 pp., more than 200 black-white illustrations, 27 colour plates).

Historical Documents in the Depositories of Georgia:

Calligraphy and Artistic Features

Despite the vagaries of history, difficulties and acts of destruction, several tens of thousands of 11th to 19th century documents in Georgian and other languages are preserved in the depositories of antiquities of Georgia. The National Centre of Manuscripts (NCM) is the greatest depository of old manuscripts and historical documents, part of which are richly illuminated. Up to 46,000 historical documents, originals and copies in Georgian, Arabic, Persian, Ottoman and other languages, are stored in the collections of the Georgian and Oriental Departments (Ad, Hd, Sd, Qd; Ard; Pd; Turd). A substantial number of documents are also preserved in the National Archives of Georgia (NAG), Ministry of Justice of Georgia– approximately 30,000 documents, of which 10,000 are original (collections: 1448, 1452, 1453). Georgian and Oriental documents are preserved in the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Art, Georgian National Museum, as well as in the regional museums in Kutaisi (ca. 2,500), Gori, Zugdidi, Batumi, and Akhaltsikhe. Also there are important collections in major foreign museums and monastic archives (Jerusalem, Mount Sinai, Mount Athos), and especially significant Ottoman documents about Georgia are preserved in Turkey and Bulgaria.

The political and cultural contacts with different countries throughout history are reflected in the material and written cultural legacy of Georgia. Because of its geographical location, Georgia has always retained close relations with both East and West. It lies at the crossroads of different cultures, which have merged and occasionally transformed the country. At the boundary of the Hellenic-Byzantine, Eastern and Western worlds, Georgia has synthesized these cultures.

The Georgian, Persian and Ottoman historical documents, preserved in Georgia and written in various languages, reflect the political and cultural changes that Georgia, as well as its neighbouring countries, had undergone over a long period of time: in the Middle Ages, when Byzantium was the primary source of inspiration for Georgia, manuscripts and historical documents reflected Christian Orthodox trends in their form, structure and artistic design. In the 16th to 18th centuries, when Georgia was divided and different areas of the country were controlled by Safavid Iran and Ottoman Turkey, the impact and influence of these preponderantly Muslim cultures were reflected in the illumination of Georgian secular manuscripts and documents, primarily Georgian-Persian bilingual documents, and also in the drawing up of Persian and Ottoman firmans. From the end of the eighteenth century, conforming to the country’s new political situation, Georgian art came under the influence of West European and Russian culture, introduced by Catholic missionaries, as well as Russian officials and ecclesiastics.

Among the major documents of the 15th to 18th centuries many examples stand out, including documents adorned with portraits of Georgian kings, ecclesiastic and secular patrons, as well as those with miniatures featuring a variety of subjects. There are also highly artistic and unique documents decorated with initials, floral, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs seen in Georgian, Islamic and European manuscript illumination. Oriental documents are distinguished by their calligraphy and tuğra, as well as by lavishly decorated motifs. Different types of documents were illuminated: Georgian – blood-money deeds, charters of grant and donation; Persian and Ottoman – firman, berat, imperial decrees, charters granting estates and documents of ritual content. Georgian and Oriental collections consist of some 200 documents, illustrating the development of the rich calligraphic and artistic heritage of the Christian and Islamic worlds from the 11th to the early 19th century.

Georgian Documents

The Georgian historical documents preserved in Georgian depositories of antiquities over a long period of time reflect the social-political and cultural changes of the historical course of Georgia and its neighboring countries. Consistent with these relations, at various stages of history, both bilingual and Greek, Persian, Arabic, Ottoman and Russian documents were created in parallel with Georgian documents of local jurisdiction.

In the Byzantine and post-Byzantine period, the content, structure and appearance of artistic design reflected the Christian Orthodox diplomatic and cultural trends. The outward appearance of a Georgian document of the 11th-13th centuries was determined by the material, form, calligraphy and decorative signatures. The illumination of Georgian documents with miniatures began from the 14th-15th century, being linked in their design with portraits of historical figures and Christian subjects. Following The fall of Byzantium and the Islamic encirclement of the South Caucasus, this tradition preserved the original and independent appearance of Georgian documents in a different political and cultural setting, distinguishing them from principles of the artistic design of Islamic documents.

Among the important documents of the 14th to the early 19th centuries, Georgian sigelions adorned with portrait images of local kings, catholicos-patriarchs, church and secular figures stand out. On blood money and donation deeds of the 14th-16th centuries the following persons are depicted: Giorgi VIII, the last king of united Georgia (king of Georgia, 1446-66; king of Kakheti, 1466-76), the kings of Imereti: Aleksandre II (1484-1510) and Bagrat III (1510-65), the eristavi of Ksani Shalva Kvenipneveli (1470), the eristavi Vameq Shaburishvili and his spouse Dulardukht (1494), catholicos-Patriarch Doroteos III (1584-95). The acts of donations and grants issued by the kings of Kartli, Kakheti, Imereti and ecclesiastics, dating from the 17th – early 19th centuries are especially distinguished for the multiplicity of donors’ images; these are represented by the following: the row of the kings of Kakheti – Levan (1518-74), Aleksandre II (1574-1605), Prince Davit (I, king of Kakheti, 1601-1602), Teimuraz I (Kakheti, 1606-48; Kartli and Kakheti, 1625-32), Prince Teimuraz (II, ruler of Kakheti, 1709-1715; King 1733-44; king of Kartli, 1744-62), Davit II Imamquli-Khan (viceroy of Khakheti, 1703-09; king, 1709-1722), Erekle I Nazarali-Khan (king of Kartli, 1688-1703), Konstantine II Mahmadquli-Khan (king of Kakheti, 1722-32), Archil II (king of Kakheti, 1664-75; king of Imereti, 1661-63, 1678-79, 1690-91, 1695-96), Catholicos-Patriarch Domenti III (1660-75), Shahnavaz-Khan (viceroy of Khaketi, 1713-23) Prince Giorgi (1712), Russia’s Emperor Peter I the Great and Empress Catherine I (1725), Giorgi XII (king of Kartli and Kakheti, 1728-1800), Solomon II (king of Imereti, 1789-1810).

In the 16th-18th centuries, under conditions of the incorporation of separate regions of Georgia by Safavid Iran and Ottoman Turkey, the impact of Islamic culture, prevalent in everyday life and all spheres of culture were reflected both in Georgian secular manuscripts and documents – in the design of Georgian and Georgian-Persian legal documents imbued with Iranian influence.

From the 18th century, conforming to the new political situation – Georgia’s incorporation in the Russian Empire, Georgian art came under the influence of West European and Russian culture; the character of artistic design of Georgian documents also changed. In this period documents adorned with geometric, floral, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs, embellished initials, as well as heraldic images corresponding to European and Russian miniature became widespread.

Persian documents

The collection is represented by lavishly designed firmans and hoqms, various legal acts, imperial decree, charters granting estates and documents of ritual content issued in the 16th-19th centuries by the Iranian royal court (Safavid, Avshar, Zend, Qajar dynasties) as well as by east-Georgian Christian and Islamized kings.

The majority of Persian documents preserved in Georgia are lavishly illuminated firmans of the Safavid (1501-1722, Tabriz/Qazvin/Isfahan) period, issued by Shah ‘Abbas I (1587-1629), Shah Safi I (1629-42), Shah ‘Abbas II (1642-66), Shah Sulayman I (1666-94), Shah Sultan Husayn (1694-1722) and Shah Tahmasp II (1722-32). Among these are the especially lavish and colourful firmans by Sultan-Husayn. Only the Qajar (1799-1925, Tehran) illuminated documents can compete with them in brilliance, abundance of colour and refinement.

The text in Persian documents is short. It is usually placed between an ornamented frame designed on two sides with stylized floral motifs. The text area is covered with coloured flower motifs corresponding to the frame ornament. Often a seal in a decorative frame is placed in the centre of the upper part of the illumination frame; in addition to calligraphy, this is given special artistic function. For Persian illuminated documents, ready-made Iranian artistic frames are also met; these were widely used in Islamic manuscripts of that period.

Ottoman documents

The collection is represented by documents of the 16th-19th centuries. Their addressers are the aristocracy and troops of regions conquered by Ottomans, and those dependent on the latter – of Childer Vilayet (part of historical Samtskhe-Saatabago), as well as the noblemen of Kartli (eastern Georgia), and the population subjected to the military landowning system.

Of the collection of Ottoman berats, the following stand out for high artistic and calligraphic qualities: berats issued by Sultan Murad III (1574-95), Mustafa II (1695-1703), Ahmed III (1705-30), Mahmud I (1730-54), Mustafa III (1757-74), Selim III (1789-1807), Mahmud II (1808-39), Abdulmecid I (1839-61), Abdulhamid II (1876-1909). The place of their compilation is “God-protected Constantinople” and Edine (former Adrianople). The calligraphy and tuğra of the sultan issuing the document, done in gold, blue and red ink, as well as separate decoration elements done in colour dyes impart a special magnificent appearance to these documents.

The web page is available on the website: www.illuminateddocument.ge

Tamar Abuladze

Doctor of Philology

Head of the Department of Manuscript Preservation

Collections of the Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts

The lecture on the theme – “Georgian and Foreign Collections of the National Centre of Manuscripts,” will review the manuscript collections preserved in the National Centre of Manuscripts. The review covers the different collections, such as manuscript books, historical documents, and archival material, their structures, quantities, significance, chronological frames, and provenance issues.

During the lecture, Georgian manuscript collections: A, H, S, Q – their provenance and establishment will be examined. In particular regarding the activities of the Georgian societies concerned with Georgian national affairs will be discussed:

Additionally there will be a separate talk about archival funds, their provenance, and the supplement of funds.We will also mention issues of carrying out fund affairs, concretely, how the fund is labeled and categorized, such as how letters are granted (A, S, H, marks on private collections, nominative funds and cabinets [for example, Library fund of S – Salia] so on). This is the protection and management of information on collection provenance. We will also briefly mention issues about the special list of honorable donors.

We will give information to the participants of the Summer school

Lastly, we will give information about the foreign funds preserved in the National Centre of Manuscripts (Armenian, Arabian, Persian, Jewish, Russian, etc.) and about Georgian manuscripts preserved abroad and their copies contained in the National Centre of Manuscripts.

Tamar Otkhmezuri

PhD in Philology

Head of the Department of Codicology and Textology

Research Interests: Georgian-Byzantine literary, Old Georgian translation tradition.

Number of Publications: 55

Main Publications:

Review of Georgian Manuscripts from a Codicological Standpoint: Georgian Manuscripts (12th-13th cc.)

In the history of old Georgian literature, the transitional period between the 10th and the 11th centuries is considered the starting point of a determined shift of Georgian intellectuals towards Byzantine culture. This tendency was influenced on the one hand by the political orientation of Georgia towards Constantinople, and on the other hand by the cultural and educational rise of 10th-century Byzantium Empire that attracted Georgian scholars.

The literary activities of Georgian scholars were inspired by the following factors: the tendencies of the enlightenment against the background of Macedonian and Comnenian Renaissance (the 9th-11th cc, 11th-12th cc.), i.e., the scholarly-critical manner of thought; the emergence of encyclopedic, lexicological and commentarial writings; literary-theoretical ideas; and the interest towards classical rhetoric, grammar and philosophy. These processes also influenced 11th-13th cc. Georgian book production. The rise of scholarly culture affected the attitude towards manuscript books and generally towards reading. From this time onwards books were used not only for meditative monastic reading, but also as reference material for quickly finding a particular part of the book.

The talk will focus on the structure of the 11th-13th cc. Georgian manuscripts produced in the monastic centers of the Black Mountain (Antioch Region) and Gelati Literary School (West Georgia). The following structural items as instruments for scholarly reading will be observed: the index prefacing the text, annotations and marginal notes of the manuscript, prologues, and colophons. The talk will also discuss the medieval sources (mainly prologues and colophons), which present the issues of medieval book structures and the function of its details, as well as the influence of Greek books on Georgian manuscripts.

Tedo Dundua

PhD in History

Professor, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

Georgia: Brief Historical Review

Georgia is situated in the center of the Caucasus – a crossroad of Europe and Asia with diversity of ethnical, ecological and linguistic characteristics. This specific location was a perfect chance to develop political, socio-economic and cultural relationship with different countries. On the other hand, this geo-political position determined course of Georgia’s history during the centuries – almost incessant warfare with neighbors in order to protect her independence end territorial unity.

Georgia underwent in different periods the Greek, Roman, Persian, Arabic, Mongolian, Ottoman and Russian influences. Often whole country or certain parts of her territory was occupied by those superpowers or became battlefield of their conflicting interests.

The earliest Georgian states blossomed in the south-western Transcaucasia by the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.

Two clearly outlined political centers – Kartli (Iberia) in the East and Egrisi (Colchis) in West Georgia are shaped already in the Classical period. In 4th cent. they convert to Christianity.

Starting from the end of the 8th cent. the decline of Arab dominance resulted in formation of a few political entities on the territory of Georgia. These political entities tended towards political integration by the end of the 10th – beginning of the 11th cent. Unified Georgian monarchy under the leadership of Bagrationi royal family reached its apex during the reign of David IV and King Tamar in the 12 cent.

Georgia, once one of the strongest political powers of the Near East entered the long process of decline under the occupation first by Mongols and afterwards disastrous invasions by Tamerlane. The fall of Constantinople dammed her access to the West and turned Georgia into a Christian island amidst Muslim waters. Georgian kingdom soon broke into petty kingdoms and principalities.

One of the most complicated periods of the Georgian history falls onto the 16th-18th cent. Isolated and divided Georgian kingdoms and principalities pressed hard by the Ottomans and Persians, often endangered by military raids of the North Caucasian tribes saw as an only political remedy their connection with almost neighboring and Christian Russian Empire.

Very soon though Georgians’ expectations crumbled and they got extremely disappointed with policies of Christian Russia: the Russians annexed step by step all political entities of Georgia, deported their rulers to inner regions of the Empire, annulled autocephaly of the Georgian Church and brutally suppressed repeated rebellions against them.

Georgian political elite used opportunity prompted by the international situation after WWI and declared independence of Georgia in1918. Democratic Republic of Georgia survived for 3 years until its occupation by the Soviet Russia. Georgia declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

Teimuraz Jojua

PhD in History

Senior Research Associate,

Department of Diplomatics and Source Studies,

Research Interests: Medieval Studies

Publications: 24

Georgian Epigraphy

Five Main topics will be discussed in this lecture:

Each issue discussed will be followed by examples of Georgian epigraphic monuments.

Teimuraz Jojua

PhD in History

Senior Research Associate,

Department of Diplomatics and Source Studies,

Research Interests: Medieval Studies

Publications: 24

Chronological Systems in Ancient Georgia

Six main topics will be discussed in this lecture:

Each topic discussed will be followed by chronological examples of Georgian manuscript monuments.

Ia Akhvlediani

PhD in geological-mineralogical science.

Associate Professor of Georgian Technical University

Graduate Gemologist (G.G.) of GIA

Research Interests: Mineralogy, Gemology, History of culture.

Number of Publications: 33

Main Publications:

Gemstones and Gemstone Imitations Decorated the Repousse Metal Covers of Georgian Manuscripts

Inserting manuscripts, especially liturgical Gospels, into the gold and silver cover and decorating with precious stones – is one of the ancient Christian tradition. The first written reference about covers decorated with gemstones associated with the name of the St. Jerome (384 A.D). Bigining from the 6th century we find images of gemstone decorated covers at the mosaics and other artwork objects, such as the 6th century icon of Christ Pantocrator from Saint Catherine’s Monastery and Justinian I-‘s famous mosaic of San Vitali basil from Rowena (Italy). Covers decorated with gemstones are shown at the miniature of Evangelists Matthew and Mark from Martvili Gospel (1050 BC.) and enamel medalions from Khakhuli icon.

Gemston’s purpose was not demonstrate the wealth only. Precious Stone’s Christian symbols based on their reference in the Bible and in theological comments of Andreas Archbishop of Caesarea (V century), from his treatise “Apocalypse Definitions”, as well as St. Epiphanius Cypriots (IV century) treatise about 12 gemstones of high priest Aaron’s Breastpiece. Precious stones as symbols of the spiritual qualities explains why so many gemstones set on Gospel covers and other treasures of the Church.

By US Embassy financial support K.Kekelidze National Center of Manuscripts carried out (October, 2014. – May, 2015) the project “Diagnostics of old Georgian engraved heritage (11th -13th cc. Georgian manuscripts)”. The aim of the project was diagnostic of covers of the Berta (Q-906), Tskarostavi (Q-907) and Tbeti (Q-929) Gospels and other Georgian manuscripts preserved at the National Centre of Manuscripts for its future conservation, protection and popularization. Gemological reserch was part of this project. 18 repoussé covers were studied. 919 gemstones dcorating them were identified.

Analysis of the gemstones was performed by portable gemological testing instruments. Gemstones used for dacoration of manuscripts are usually mounted in closed settings, therefore the rear side is not available for inspection. Stones arrangement, as well as their surface condition eliminates the use of refractometer. The equipment, which need transmitted light is out of work. Therefore, the main attention should be paid to the external appearance and inclusions of gemstones. Effective was thermal inertia tester and hand spectroscope combained with professional UV fluorescent lamp for distinguish red gemstones – ruby, spinel and garnet (almandine), as well as to reveal the glass.

Following natural gemstones were identified on the repousse covers: amethyst (1 case), pink spinel, ruby, blue sapphire (2 cases), pink sapphires, red garnet – almandine (almandini estimated by spectroscope and hand-held XRF analyzer ), coral, color change parple and violet sapphires, star sapphires and ruby, turquoise, cornelian, blue chalcedony, emerald and green beryl, peridot, rock crystal, iolite (previously described as a blue sapphire). Most of the stones have easily recognizable typical inclusions. Some of them contain inclusions indicative of their origin: ruby from Ceylon and Burma; sapphire from Ceylon; emeralds and green beryls from – Colombia mines.

A lot of gemstone imitations were used to dacorated manuscript covers – colored glass or foiling colorless glass (sometimes rock crystal). Over the past centuries, blue glass or blue foiled glass imitate sapphire crystals, the green – emeralds, the red – ruby.

Turquoise has the most imitations. Imitation may be opaque turquoise blue glass, ceramic masses, sintering products. In 1872 Ekaterine Chavchavadze coverd gospel and adorned with gems, which at first glance looks like turquoise. Our study shows turquoise imitation popular in the 19th centuryv – crumbled, deposited and pressed under pressure material.

XVIII century European glass manufacturers have found that lead oxide additive trengthens glass shine and dispersion. The glass, which is used to imitate the diamond, called “strass”. Repoussé covers H1689 (1799), Q 895 (1826) decorated with painted enamel medallions surrounded by strass .

Of special note are three glass studes on Tskarostavi Four Gospels – 2 blue cabochones on the top and 1 dark yellowish-green plate on the lower wing. Because it means the XII century and the “Byzantine” epoch in the history of glass melting. Composition of “Byzantine glases” should be particular study subjects.

Pearls in X-XII centuries used to highlight the colorfulness of the gemstone and they only surrounded gemstones. In XVI-XVII centeries pearl occupies an independent seat – set by small nail or in metal casing.

Pearl dacoration partially maintained on Berta Gospel and Alaverdi Four Gospels. With high probability strings of pearls dacorated Tskarostavi Four Gospels (Q-907): eyelets for fixing strings survive. There is a written notice about the existence of pearl decor.

Levan Gigineishvili

Doctor of Philology

Professor, Ilia State University

Medieval Georgian laic literature

Georgian literature from the time of its inception in 4th-5th centuries to 11th century was exclusively purposed to a religious-ecclesiastic tasks in all its genres – hagiography, hymnology, homiletics, theological treatises and even historical writings, which presented the history of the Georgian kingdom in terms of the Biblical providential history.

However, the situation started to change from 11th century onwards, when first philosophical works were translated from Greek and Georgian philosophical terminological apparatus was formed. The Gelati monastic school established in early 12th century took an initiative of translating philosophical texts already for their own sake and not just for serving the purposes of the Church. Ioane Petritsi, the greatest philosopher of the Medieval Georgia par excellance represents this new trend in Gelati, for he translated Proclus’ “Elements of Theology” having supplied it with his original commentaries in which he communicated to his students the basics of the Greek philosophy and Platonic metaphysics.

Petritsi’s lead was taken by Shota Rustaveli, the author of the chivalrouw epic “The Knight in Panther’s Skin”. Rustaveli expanded his horizon not only to the Greek culture, but also to the Persian culture – its poetry and the Sufi mysticism. With such a broad scope of ideas and traditions, Rustaveli managed to create a novel vision of the world, which in few important and essential traits is similar to what happened in Europe a couple of centuries afterwards, during the Italian Renaissance. With Petritsi and Rustaveli, indeed we can speak about a Georgian pre-renaissance that was regrettably interrupted by the Mongol invasion in late 13th century.

Maia Karanadze

PhD in Philology

Senior Research Associate,

Department of Codicology and Textology,

Her PhD was dedicated to the investigation of Georgian Book-covers: “From the Georgian Written Language History (Manuscript Book Covers as a Part of the Codicological Research)”- 1995. She is an author of monograph “The History of Georgian book-covers”, Tbilisi 2002. Maia Karanadze is a co-participant of the project “Georgian manuscript book (creation of a web-page)” www.geomanuscript.ge and co-author of the book “Georgian manuscript”, Tbilisi 2012.

Her hobbies include working with Cloisonne enamel. Her enamel patterns are inserted in the catalogs. She participated in several international Biennials. Maia Karanadze’s masterpieces are preserved in different collections of Georgia and abroad.

Manuscript Book Cover

The history of Georgian manuscript book cover leads us to the origins of our literature. The Khanmeti palimpsest dated to 5th – 8th cc. has traces of note-book pagination. This means that the book was bound in the 5th century.

Archaeological excavations carried out in Kakheti give an interesting notification about parchment formation. Stamped processing of the parchment was developed in the middle Bronze Age. Triangular, stamped banners have been found. Supposedly, the parchment cover could be stamped in the 5th \ century.

”Binders” worked in churches and monasteries. Sometimes the book copyst was also the cover maker.

Creators of Georgian manuscript books had close contacts with Byzantine, Armenian, Eastern, Euripean, Russian and other literature centres.

Two processes of book binding – binding and attaching wooden threads – was one complete and combined work for Georgian monks, who lived and worked on Mountain Sinai in the 10th c. and that was called ”Georgian sewing” by Bert Van Rejemorter.

As a result of material systematization, three conjectural stages of Georgian manuscript book cover development were identified: Early, Transitional and Latter.

For covers of the Early period (X-XVI cc.), the following are characteristic: Correctly sliced massive wooden boards, cut on the face of manuscript sheets. Smooth spine, that is received with technique of Grekaji (slot of the shape of V on spine). ”Linear” and ”wicker”ornaments as well as other kinds of stamps are used in decors.

Transitional (XVII c.) wooden boards of covers are unchanged, relief places of binding appears on the spine.

The participation of the secular aristocracy in the creation of manuscript books from the XI c. to the XIX c. contributed to the creation of richly decorated stamped covers. The famous goldsmiths Beqa and Beshqen Opizars lived and worked in the XII c.

Book covers made with combination of parchment and blacksmith’s details appear in the XIV c.

The beginning of the XVIII century is the period of Georgian cultural life when printed books apeared alongside manuscript books (Gospel, 1709). It is also an important fact that the printing – press in Georgia comes from Romania.

Latter (XVIII- XIX cc.) The appearance of Georgian book covers is obviously changed. Indirectly sliced wooden boards dismounts and covers the whole book body. The spine is raised. Stamps consisting of thematic, leafly – flower and geometric pictures appears in the decor. The book cover has an European influence.

Mzekala Shanidze

Doctor of Philological Sciences. Academician

Academician of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences

Research Interests: Linguistics, Morphology, Lexicography, Textology, Publicaton of Old Georgian Texts, linguistic – Textologic Analysing of Georgian Biblical and Original Texts.

Publicatons: approx.150, among them 12 are in Foreign Language and are Published Abroad.

Main Publicatons:

Textological problems in Georgian Manuscripts

The lecture presents textological problems arising in the process of studying old Georgian manuscripts with the aim producing a definitive text for publication. Some specific features of this work are discussed such as facts concerning the history of Georgian literary language, the character and number of the existing manuscript and their choice, etc.

Examples of various literary and historical texts are cited and the works presenting the most difficult problems are discussed – Shota Rustaveli’s poem “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”, Kartlis Cxovreba (History of Georgia), old Georgian biblical texts, and the works written in the pseudo archaic language in the 18th century.

Hubertus F. Jahn

Dr. phil. habil. in Russian and East European History

PhD in Russian History

MA in History and Slavic Studies

Reader in the History of Russia and the Caucasus

Faculty of History, University of Cambridge

Fellow, Clare College, Cambridge

Research interests: Social and cultural history of Russia, history of the South Caucasus

Number of publications: 44

Main publications:

Sources about Georgia and the Caucasus in Russian Archives

Georgia and Georgians have left many traces in archives around the world as a result of diplomatic relations, personal contacts, trade, cultural and religious exchanges or dynastic links. Sources of the Georgian diaspora, although not as big as the Armenian one, can be found in foreign archives as well. Furthermore, Georgia has not always been an independent country. At times it belonged to different empires. Materials about Georgia are consequently conserved in larger quantities in the archives of neighbouring countries, such as Turkey, Persia, and Russia.

The talk will focus on materials related to Georgia in Russian archives. It will look at some of the fondy of the Russian State Historical Archive in St. Petersburg, which holds the files of various departments of state of the Russian Empire, of various committees and commissions, of the Imperial Court, the Academy of Arts, the Chancellery of the Holy Synod as well as various archives of famous individuals. There will also be an opportunity to discuss practical aspects of working in archives in Russia today.

Khatuna Gvaradze

PhD in History

Researcher, archivist

Wittgenstein Archive, Cambridge

Research Interests: Georgian medieval and modern history and gender studies in the Caucasus.

Number of Publications: 12

Main Publications:

Sources about the Georgian women’s movement

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

The women’s movement in Georgia had a rather specific character. Its main peculiarity was that women’s issues were fused with national interests, and Georgian society viewed the social initiatives and activities of women as part of the wider conflict with colonial policies of the Russian Empire. Nonetheless, the Georgian women’s movement has its own history which was very much connected with the ideas and values that were brought to Georgia by both women and men educated abroad either in Western countries or in Russia as well as with the translations of foreign literature about social and political rights of women. The chronological timeframe of my topic is deliberately chosen to end in 1917, because the Bolshevik regime tackled the women’s question quite differently from the 19th century “bourgeois” women’s movement.

The main sources for understanding the Georgian women’s movement and for reconstructing the historical situation of women’s conditions and their level of emancipation in 19th and early 20th century Georgia are contemporary journals and newspapers, which are all kept in the national parliament library of Georgia. The talk will also focus on original and translated literature by women and about women, which strongly influenced the women’s movement in Georgia. Furthermore, records of proceedings of women’s organizations and their annual reports reflect the character, the motives and the aims of women’s activities, showing the different experiences of various social classes, from educated members of the intelligentsia to illiterate peasant women. Finally, biographies of female public figures and writers, whose private archives are kept in the Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts and in the Giorgi Leonidze State Museum of Literature will also be considered.

Nino Jishkariani

Graphic Artist, Graphic Designer

Lecturer at the Media-art Faculty of Font and Ornament, Tbilisi State Academy of Arts

Founder of the “Georgian Font” Association

The Brief History of Georgian Font Developments and the Core of Problem

If we look through the history of Georgian typographic fonts, we see that the fonts, or the movable letters, were not created at once. The development of writing had a great influence on the formation of these fonts on a certain level. Our ancestors were very well aware of the importance of writing, developing it with great love and energy according to their time. Along with the development of printing facilities, the typographic font was gradually liberated from the influence of handwritten letters, gradually parting the ways for the development of writing and book-printing.

The first Georgian typographic font was made in Rome, according to the alphabet of the letter, which Teimuraz the first had sent to the head of the Catholic Church. With this type, in 1629, Stefano Paolini compiled and printed the Georgian-Italian Dictionary to be used by the missionaries that traveled to Georgia. This font did not provide the characteristic features of the Georgian Alphabet outline and proportions. In 1709, King Vakhtang VI founded the first printing house in Georgia. Vakhtang typographic fonts stood on a much higher level of graphic performance compared to the Roman fonts. The shifting of geopolitics conditions of our small country also influenced the font development.

Georgian polygraphy center finally moved back to Tbilisi from Russia and European cities in the second half of the 19th century. New publishing houses fostered the wide development of book-printing. One of the figures of this period was the first engraver Grigol Tatishvili, whose most prominent work of art was the decoration of The Knight in the Panthers Skin, issued by G. Kartvelishvili in 1888.

After the establishment of Soviet power in Georgia, the publishing houses and printing workshops were nationalized. State Publishing House was created, forming the Poligraptrest, which was assigned to work on the issues of type culture and polygraphy. In 1947, Georgian Font Committee was established. Since 1950, Georgian typography began to rise, enriched with new text and title fonts. At that time, this field had the most governmental support, very much needed for this business, from the State Laboratory of Fonts.

The artists did not spare efforts for the development of this field. One such example would be Lado Grigolias fundamental works: the Academic Font and its System of 396 Variations (1951-1955), the the Artistic Fonts and Ways of Creating them, the font tables for posters, polygraphy, teaching and so forth.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the state could not pay proper attention to typography due to the changes of political situation and governments during this period. The font development was more or less stalled. The first complete catalog of Georgian typographic fonts was released in 1965 (compiler – Beno Gordeziani). Since then, no complete catalog was published, with the exception of certain catalogs, for example Lado Grigolias the Basics of Georgian Font Art (2004, the author – I. Divnogortseva-Grigolia), or the album-monograph Georgian Book Art, which included the 20th-century title fonts (2013, the author – N. Jishkariani).

Today, Georgian font condition looks encouraging. In 2015, the association Georgian Font held the Font Exhibition, displaying both old and modern fonts samples. The exhibition has proven once again what a great treasure we possess in the form of old printing and drawn fonts, which urgently needs digitalization, and shown what we have today in this regard. Also, recently, with the support of TBC Bank the fonts contest was arranged. Hopefully, this revival too will foster the developments of types/fonts in future.

Nikoloz Aleksidze

Junior Research Fellow, Pembroke College Oxford

Research Associate, History Faculty Oxford

Dean of Social Sciences, Free University, Tbilisi

Georgia and the South Caucasus: Unity, Diversity and Memory

Georgian or Kartvelian studies is often perceived as an integral part of a larger area, conventionally known as Caucasian studies, a scholarly field that covers medieval Albanian, Armenian and Georgian history. Indeed, a proper understanding of Georgia’s history and literary production requires a good knowledge of related processes in the neighbouring areas and particularly in medieval Armenia.

The lecture will briefly explore the formation of medieval historical and identity rhetoric in the South Caucasian region. Several questions will be addressed pertaining to the problems of ethnic, political and religious identity discourses formed among medieval Armenians and Georgians, more precisely how the two nations defined Georgianness and Armenianness throughout the centuries. How did the ethnic and religious markers function in the medieval Caucasus? Did they occasionally overlap? What role did Armenia and Armenians play in medieval Georgian political rhetoric and vice versa, what place did the Georgians occupy in the formation of Armenian rhetoric?

The usage of the past as a rhetorical device is particularly observable after the ecclesiastic separation between Armenians and Georgians, which occurred in the early seventh century. During the ensuing ardent religious debates and political controversies, the intellectuals of both nations attempted to create usable pasts and forged grand narratives of their respective nations. Images of the self and the other were created and reproduced in every instance were past needed to be replicated and imagined for the immediate purposes of the present. The political status quo required interpretation and for this purpose interpretive schemata were created, which not only gave the past a meaning but also reshaped the past in order to sustain clarity and continuity between the obscure past and the problematic present.

Mzekala Shanidze

Doctor of Philological Sciences. Academician

Academician of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences

Research Interests: Linguistics, Morphology, Lexicography, Textology, Publicaton of Old Georgian Texts, linguistic – Textologic Analysing of Georgian Biblical and Original Texts.

Publicatons: approx.150, among them 12 are in Foreign Language and are Published Abroad.

Main Publicatons:

The Georgian Language

Terms for Georgian and Georgia in Georgian languages (Kartveli, Kartuli, Sakartvelo).

European and Oriental terms for Georgian and Georgia (Gurji, Georgia) and their origin, area of spoken Georgian and its dialects. Georgian and languages of the Kartvelian linguistic family. Attempts of classifying the relationship of Georgian to different languages (Basque, dead languages of the Near East).

Georgian language and its phonematic structure at the time of the origin of the Georgian alphabet. Stages of development of Georgian. Ancient Georgian. Middle Georgian and modern Georgian. Historical changes in Georgian – changes in morphological structure and vocabulary. Georgian Language in the 18th – 19th centuries. Ilia Chavchavadze and new schools of thought. Modern literary language.

Mzia Surguladze

Doctor of Historical Sciences

Head of the Diplomatics and Source Studies Department

Research Interests: Source Sudies

Publications: 50

Main Publications:

Conceiving Time and Space According to Historical Documents of Medieval Georgia

There are more than 60, 000 Georgian and foreign historical documents of the 10th to 19th centuries at the National Centre of Manuscripts. Among foreign documents there are also Persian and Turkish funds and multiple collections of Russian and European documents which reflect political situations not only about Georgia, but about the South Caucasian countries and their significance in an international context.

Historical documents contain information about diplomatic correspondence, judicial acts, orders, and directives given by kings, political and ecclesiastical leaders. No other historical sources contain such rich information about social development and administrative arrangements of state than historical documents. These documents are determined by particular scientific values:

During the medieval times, historical documents reflected the political system, Christian ideology, and system of values in Georgia.The content of the historical documents (the structure, stereotypical phrases, and formulas) determines a specific structure of the text. Therefore, these documents differ from other historical sources. Because of this reason scholars and scientists use different methods to reveal the different information contained in the documents.

Nino Kavtaria

Doctor of Art History

Head of the Art History Department

PhD in Art History and Theory

Research interests: Georgian illuminated manuscripts, their iconographic-stylistic an artistic features, and the interrelation and influence of Byzantine and East Christian Cultures on the Georgian illustrated manuscript. Fellowships for several research projects on the art of the Georgian book at Warburg Institute, IKY, CEU, DAAD, Koc University.

Number of Publications: 30

Main Publications:

Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium of Georgian Culture “The Caucasus: Georgia on the Crossroads. Cultural Exchange Across the Europe and Beyond,” Tbilisi, 2011, p.125-131.

Miniature and Décor in Georgian manuscripts

This is a lecture course in the history of Georgian Book illumination from IX century to the XVIII century. We plan to familiarize participants with the Art of Georgian Book illumination and cultures of East Christian World. Participants will also gain knowledge about Islamic influences in Georgian manuscript illuminations. During the lecture we will mainly trace the art styles and principle periods of Georgian book illustrations. We will also note briefly rise and development of book illustration in general.

Main goal of our lecture is: to introduce the basis shape and tendencies of Georgian book illumination, including periodization, major features, iconography, local leanings, as well as interaction of different cultural influences on Georgian manuscript Illustrations; to become familiar with the features of Book illumination in general outline, and specifically Georgian miniature painting.

To help the participant understand Art of Georgian manuscript Illumination within the context of time, place, society, circumstance and etc.

To explain main developments in Book Illumination from Early Middle Ages through the Late Middle Ages in Georgian reality, with foreseeing of surrounding countries’(Byzantine, East-Christian and Islamic) miniature art.

The lecture based on the study of Georgian manuscript patterns survived in Georgian Museums and in K.Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts.

The lecture consists of several general topics on the Art of miniature and décor:

Nana Targamadze

Head of the Department of the Library-Museum

Research interests: History of the Georgian printed book; Rare publications and old printed Georgian books; Georgian printing-houses

Number of Publications: 5

Main Publications:

Annotated bibliography of the editions of National Center of Manuscript; catalog of manuscripts and editions of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”; for the history of printing-house of Vakhtang VI

Old Georgian Printed Books (XVII -XVIII cc.)

The first books with Georgian printed texts were printed in Rome in 1629, they were: a Georgian-Italian dictionary, a Georgian alphabet with prayers, and a “Litany Lauretana”- a prayer dedicated to the Virgin.

These books were published with the intention of propagandizing the Catholic faith. In this period (beginning of the XVII c.), Catholic missionaries of Rome were interested in learning the Georgian language. Nikifore Irbakhi and Nikoloz Cholokashvili with Stepane Paolin were mentioned as the authors of the Georgian-Italian dictionary on the title page, which was printed in the Italian language.

Nikofore Cholokashvili, an ambassador of Teimuraz I in Europe, was an educated language expert, a compiler of “Georgian alphabet and prayers”, a translator of “Litany Lauretana” from Latin to Georgian, and a participant in the casting of the first Georgian font, Mkhedruli.

Five various Georgian Editions are known among the books printed in Rome during the XVII c. For instance, a ‘Grammar of Georgian Language’ book by Maria-majio was published twice in 1643 and 1670.

There was an attempt to establish a Georgian printing press in Georgia. At the end of the XVII c, Archil II (already an emigrant to Russia) with Prince Alexander, arranged the casting of the Georgian font in Sweden. “Psalms” was printed in the Georgian language in Moscow in 1705. The printing of Georgian books in Russia began with it.

In 1709, Vakhtang VI’s printing press was founded in Tbilisi, a special event in the development and history of Georgian national culture.

Vakhtang VI’s printing-press existed for 13 years. The success of its operation was influenced by several factors: the professionalism of Mikheil Ishtvanovichi (skilled print-worker); the devotion of Georgian print-workers (Nikoloz Orbeliani, son of deacon Miqel, painter George, priest Gabriel, and Joseph Samebeli); intelligent work; mastery of sorting text technically; high quality of interpolated engravings, font and printing paper.

Twenty editions were printed in Vakhtang’s printing-press. We must think that the editions of Vakhtang’s printing-press did not completely reach our period. In 1722, the deterioration of the political situation forced Vakhtang VI to seek shelter in Russia.

Book printing was obstructed over a quarter of a century in Georgia, but it continued to develop in Moscow. The first book “Psalms” was published in 1737. Georgian emigrants arranged the publication of eleven thick books over seven years. In 1743, they printed a Bible and compositions translated by Arsen Ikaltoeli.

The Georgian font was being prepared for the printing-presses of Moscow in St. Petersburg under the leadership of the great figure Kristefore GuramiShvili. The printing-press was organized at a scientific academy of St. Petersburg also under his leadership (1736-1737). A Russian-Georgian alphabet with prayers, texts of Latin prayers and German remarks was printed in this printing-press (preserved only in St. Petersburg).

Books of the printing-press of Moscow were influenced by the Russian printing-press. Originality remained only in the design of the emblem of Bagrationi. The printing-press of Moscow used only the Nuskhuri font.

In 1749, during the reign of Erekle II, profitable conditions were made for the restoration of printing-press. Anton I played a decisive role in this work (up to 40 books were printed in Erekle’s printing-press, that was basically reiterating the editions of Vakhtang’s printing-press).

“Psalms” was published in 1749: Erekle’s printing-press operated until 1795, before the invasion of Aga-mahmad-khan.

In 1800 the Georgian printing-press was restored for the third time. Only two editions were published in the new printing-press: the book of akathistos and a “study” of Prince David.

Attention must be paid to the fact that the printing-press was started up (1796-1801) on the initiative and at the expense of the rector, who was living in Mozdok. The great master of printing-press Romanoz Razmadze-Zubashvili was living and working in Mozdok. Four editions were printed. Among them was “Albhabet” of Gaiozi, a sample of printing art.

The first printing-press in Imereti began operating in 1800.

In 1779, Solomon II specially sent the print-worker Giorgi PAichidze to Moscow. The first book “Psalms” was printed in Kutaisi in 1800.

Romanoz Razmadze-Zubashvili began working in Kutaisi in 1803. The printing-press of Imereti began to operate in Tsesi and in 1815-1817 printed books on the door of Zurab and Grigol TSereteli in Sachkhere.

This is a short review of the development of the history of the Georgian printing-press.